Lai Nguyen, his wife Thuy and his teenage daughter Tham usually spend their nights cooking, packing and serving delicacies such as aromatic duck, yuk sung, and spicy prawn coconut soup to customers at their family business, the Clarehall Chinese Takeaway in Dublin.

This week is different, at least for Lai and “Thammy”.

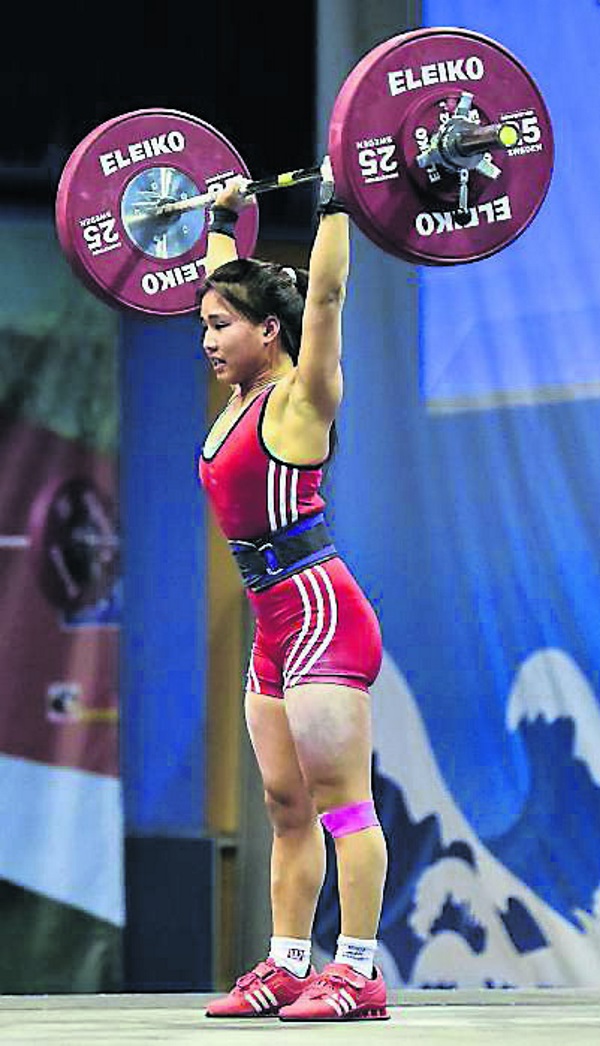

At about 9pm Irish time tonight, Thammy – all 7st 7lb of her – will walk on to the stage at the George R Brown Convention Centre in Houston, Texas, and do something no Irish female has ever done before. She will compete at the weightlifting World Championships.

It is a remarkable achievement for Thammy, or “Miss Muscles” as her friends call her. Until September last year she had never competed at any level in weightlifting.

Her long-term aim is to make it to the Olympics – with her 15-year-old brother Nhat, one of Ireland’s top badminton players. Tokyo in 2020 is the target.

Ireland has sent four women and one man to Houston. Lai will be there to watch Thammy, 19, which is another first.

She has won competitions, set national records, competed in the European Junior Championships but neither of her parents has ever seen her lift.

“To start with, me mam was against it,” says Thammy, who is fluent in Vietnamese but whose accent is pure Dublin.

She moved here with the family when she was seven.

“I’d come home with bruises all over my neck [from practising the clean & jerk lift] and she said it wasn’t a sport for a girl, not feminine.

“Now my parents are fine, but they work such long hours in the takeaway they’ve never seen me lift.”

That wariness about weightlifting has dogged the sport for years, but it is changing. Contrary to popular perception, weightlifting does not give girls a deep voice and lumps in all the wrong places.

One of the women in the British team in Houston does modelling work and was voted Miss Leeds a few years ago.

More important, says Ireland’s national coach Harry Leech, “there’s a new openness about strength and conditioning in women’s sport”, and there is the boom in Crossfit, the gym-based competitive fitness sport.

It started in the US and has grown from 18 gyms to 13,000 worldwide in the past 10 years.

Olympic weightlifting is a big part of Crossfit and many athletes enjoy the lifting so much, they take it up seriously, which led to a huge increase in registered lifters in all parts of the world.

Ireland had barely any a few years ago: now there are 500 who compete regularly.

“I would watch people lifting weights in the gym when I was 16, and I started copying them,” says Thammy.

“Then last year I was on instagram and I saw this girl in great shape, she had a six-pack and I liked that look. I mailed her and said ‘How do you get like that?’

“She said she did it at Crossfit, so I joined a Crossfit gym in 2014, in April.

“My very first day of Crossfit was an Olympic lifting day and my coach watched me.

“I didn’t know any technique and I couldn’t even lift the 15kg bar, I had to use a light bar.

“I had no upper body strength – all my strength was in my legs.

“He showed me what to do and after only four or five minutes he said: ‘You’re a natural.’ I was soon lifting 85kg.

“The gym had only been open three months and I was the first girl to lift 85kg.

“By September I had taken up weightlifting and now I’ve stopped Crossfit.

“I was never in touch with that girl again but I should find her and say thanks, because without her I wouldn’t be going to the World Championships!”

While Thammy is the only “Crossfit exile” in the team the other three women all moved over from other sports.

Alexandria Craig, 30, who lifts in the same 48kg weight category as Thammy, was a gymnast and circus acrobat.

At 58kg Emma Alderdice, 23, started lifting to improve her strength for volleyball, and 30-year-old Aoife MacNeill was a top 100m and 200m sprinter.

The sole man is Cathal Byrd (29), Ireland’s most experienced international lifter.

None of the team is expected to challenge for a medal but they can chase personal bests and national records.

Women first competed in the World Championships in the 1980s but were not on the Olympic Games programme until 2000.

“A dozen years ago we barely had any women – we’d have been happy with double digits,” says Leech.

“This year is the first time our women have reached the standards needed to compete at the World Championships.

“Other sports talk about the good old days, the golden years, but there never were any good old days in Irish weightlifting.

“Everything is happening right now.”

But there is still a long way to go. Funding is a big challenge. The Houston team have to raise 70-80% of their own costs.

For Thammy, that has meant working four or five shifts a week at the restaurant, plus doing women’s eyelashes (“I taught myself first then took a course”).

Given she is a student at Portobello Institute, in sport science and PE, and she trains five days a week, that means when she is not sleeping she is busy almost every hour of every day.

Even so, she still has time for the occasional night out with friends – “they all call me Miss Muscles” – and has been with boyfriend Paul Darcy for three years.

“He likes Crossfit but he doesn’t compete, he’s the opposite of me,” she says.

“He drives me up and down the country and really believes in me. He knows I get stressed out sometimes and I take it out on him but he understands and lets it pass.”

If she is to realise her ambition and compete at the Olympics she will have to work even harder, and for a long time.

“There’s no doubt that Tham has potential,” says Leech, who has put in thousands of hours as a volunteer over the years, and spent about €30,000 of his own money.

“But reaching full potential in this sport requires dedication, hard work, the right support structure for a decade or more, as well as some good luck.

Qualifying for the World Championships is a great achievement, but actually capitalising on that potential is the real challenge.

“There is no precedent of anyone starting this sport and being a medal winner at a senior international with a few years work. It’s a decade or more of commitment.”

Courtesy of: Irish Examiner