In 2016, six years after he began a painstaking search for a woman in an old photograph, Professor James Kimble found himself, flowers in hand, at Naomi Parker Fraley’s house in California.

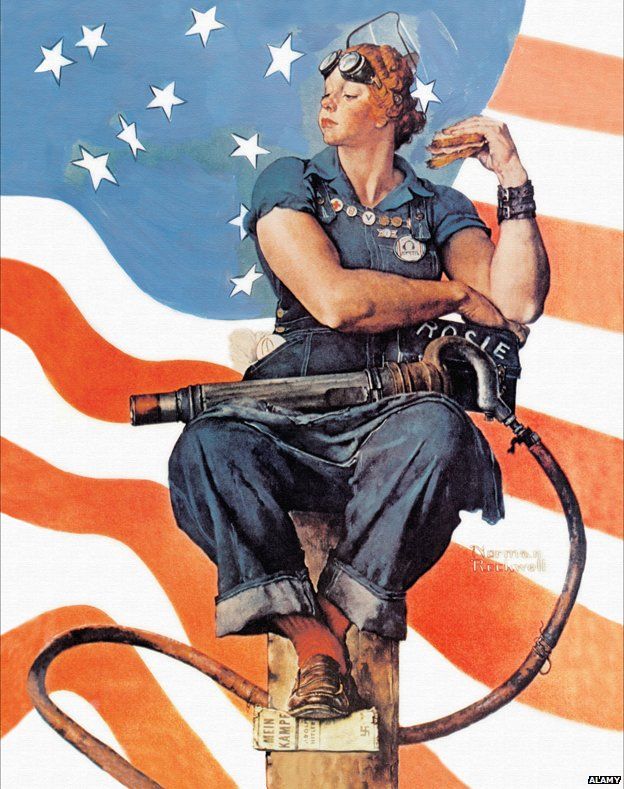

He believed that Parker Fraley, who died on Saturday aged 96, in Longview, Washington, was the inspiration for Rosie the Riveter, a poster that became an enduring symbol of American feminism and one of the country’s most iconic images.

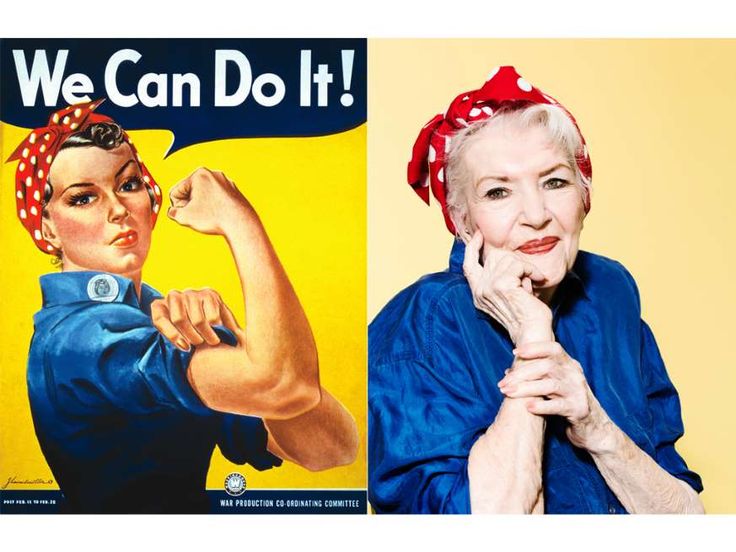

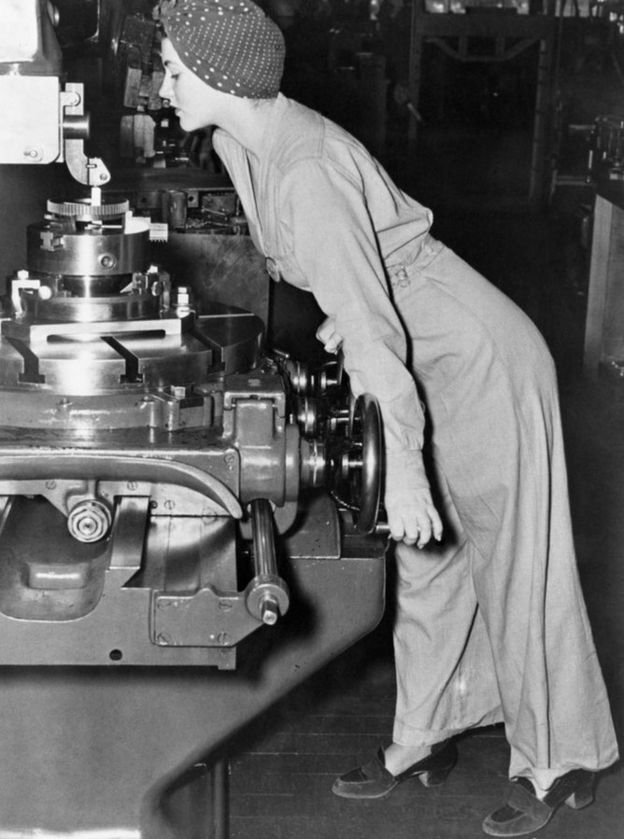

The poster, by the Pittsburgh artist J Howard Miller, depicted a wartime woman worker in a blue shirt and a red polka-dot bandanna, flexing her bicep, with the caption “We Can Do It!”. Miller’s poster is thought to have been based on a photograph of a woman standing at a lathe which was published by a number of magazines in 1943 but seemingly never captioned with a name or a date.

Mr Miller’s poster went largely unnoticed at the time – it was displayed only in-house at Westinghouse electric plants – but it became an icon decades later, printed on everything from T-shirts to fridge magnets to skin, and reimagined by the singer Beyonce, the New Yorker magazine and others.

But as the image became ubiquitous, Parker Fraley went unknown. Another woman, Geraldine Doyle, a wartime metal presser at a Michigan industrial plant, thought she saw herself in the original photograph and her claim was widely accepted.

When Doyle died in December 2010, obituaries were published by the BBC, New York Times, and many others.

Image copyrightBETTMANN ARCHIVE

Image copyrightBETTMANN ARCHIVE

But something about the story did not sit right with Mr Kimble, an associate professor of communication at Seton Hall University in New Jersey. He had previously researched the poster and published a paper debunking some of the myths around it.

“I had said in that research that almost everything we know about that poster is wrong,” Mr Kimble told the BBC in a telephone interview. “So when Doyle died in 2010, and there were all these obituaries, I of course thought, how do we know she’s really the model? What’s the proof? It was the rabbit hole calling to me.”

For six years, Mr Kimble scoured the internet, magazines, and wire services, searching for a version of the image with a caption. Then in 2015, he found another image of Parker Fraley, and via a reverse image search traced it to a vintage newspaper picture dealer.

It just so happened the dealer had a companion image from the same day, and it was the woman at the lathe. More importantly, it had a date – 24 March 1942 – a location – Alameda, California – and a caption.

“Pretty Naomi Parker looks like she might catch her nose in the turret lathe she is operating,” it said. The women wore “safety clothes instead of feminine frills”, it added, “And the girls don’t mind – they’re doing their part. Glamour is secondary these days.”

Naomi Parker was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma in August 1921. She was the third of eight children to Joseph Parker, a mining engineer, and Esther Leis, a homemaker. The family moved from town to town, following mining work, before settling in Alameda.

In 1942, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, 20-year-old Naomi went to work at the Naval Air Station in Alameda alongside her 18-year-old sister Ada. It was in the workshop there that she was captured, by a photographer for the Acme photo agency, leaning over the lathe.

When the picture appeared shortly after alongside an article in the Oakland Post-Enquirer, Parker Fraley carefully cut out the article and kept it for 70 years, while the world misidentified Doyle in her place.

After the war, Naomi and Ada worked as waitresses at a famous Palm Springs restaurant, the Doll House. She went through two marriages and two divorces before marrying Charley Fraley, a brick mason, in 1979. Then after Charles died in 1998, the sisters moved in together in California.

Parker Fraley had seen the famous poster – “I did think it looked like me,” she said later in an interview with People Magazine – but she did not connect it to the newspaper photograph stored away among her keepsakes.

Then in 2011, at a reunion event for female wartime workers, Parker Fraley for the first time saw the poster displayed alongside the photograph. The woman in the photograph, according to the information alongside, was one Geraldine Doyle.

“I couldn’t believe it,” she told the Oakland Tribune in 2016. “I knew it was actually me in the photo.”

When he first read the caption naming Parker Fraley, Mr Kimble assumed she was dead and set about trying to track down relatives through a genealogical society. After a few months, they sent him back a note saying their ethics rules did not allow them to share information about people who were still alive.

Eventually he found his way to her door in Alameda. With flowers in hand – “on my wife’s advice, and it was good advice”, he said – he rang the bell.

“She was just so excited and thrilled that someone was there to listen to her story,” Mr Kimble said. “By that point it was three or four years she had been aware that her photo was out there under someone else’s name. No matter how hard she tried, no-one would listen to her.”

After his discovery was made public, the Omaha World-Herald asked Ada down the phone – Parker Fraley is hard of hearing – how it felt to finally be known as the woman behind Rosie.

“Victory!” Parker Fraley could be heard yelling in the background. “Victory! Victory!”

The connection between the photograph and Mr Miller’s poster is not ironclad – there is no documentation to prove it was the artist’s inspiration. But the picture was published widely the year before the poster was created, including the Pittsburgh Press in Mr Miller’s hometown, and to many the striking resemblance of Parker Fraley’s distinctive workwear is enough.

One thing is for certain, after all these years: the woman at the lathe in Alameda, California was Naomi Parker Fraley.

“It was an absolutely joyful day when I went there,” said Mr Kimble. “I would have to say it was the highlight of my career to have the privilege of talking to her.”

Parker Fraley is survived by a son from her first marriage, Joseph Blankenship, as well as four stepsons and two stepdaughters from her marriage to Charles Fraley.

“The women of this country these days need some icons,” she told People magazine in 2016. “If they think I’m one, I’m happy.